Tracing the Crown: A Collector’s Journey Through Rolex History (1905–2000)

Hans Wilsdorf, founder of Rolex, nurtured a revolution in wristwatches.

Beginnings in an Era of Pocket Watches (1905–1919)

Rolex’s story begins with a young man’s audacious dream. In 1905, a 24-year-old Hans Wilsdorf teamed up with his brother-in-law Alfred Davis in London to establish Wilsdorf & Davis, the company that would become Rolex. Prior to this, Hans already build up an international network and gained cognizance regarding time measurement devices, due to his experience at a previous firm he worked. He also was quite mature for his age, because of a quite ‘dynamic’ youth as he became an orphin at an early age. But we will refrain from telling his personal life story and focus on the company he founded and subsequently build up.

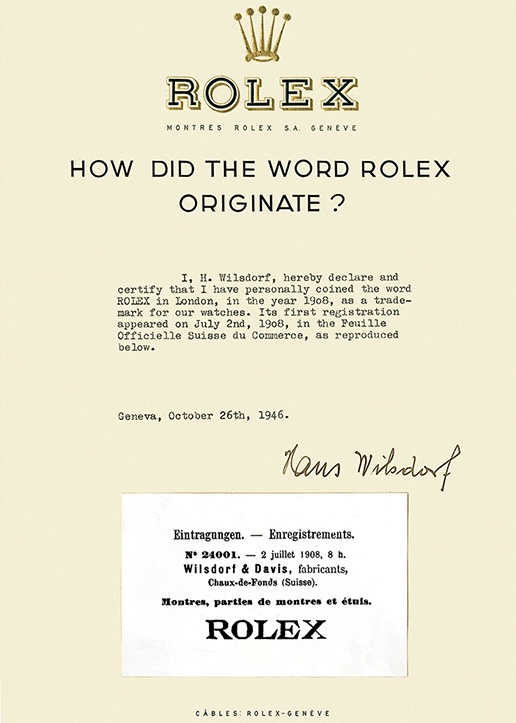

At a time when the gentleman’s watch was still a pocket watch, Wilsdorf believed the wrist-watch had a future; eventohugh others were skeptical. By 1908, Wilsdorf had coined the brand name “Rolex”, deliberately short, snappy, and easy to pronounce in any language. Just like Kodak for camera’s.

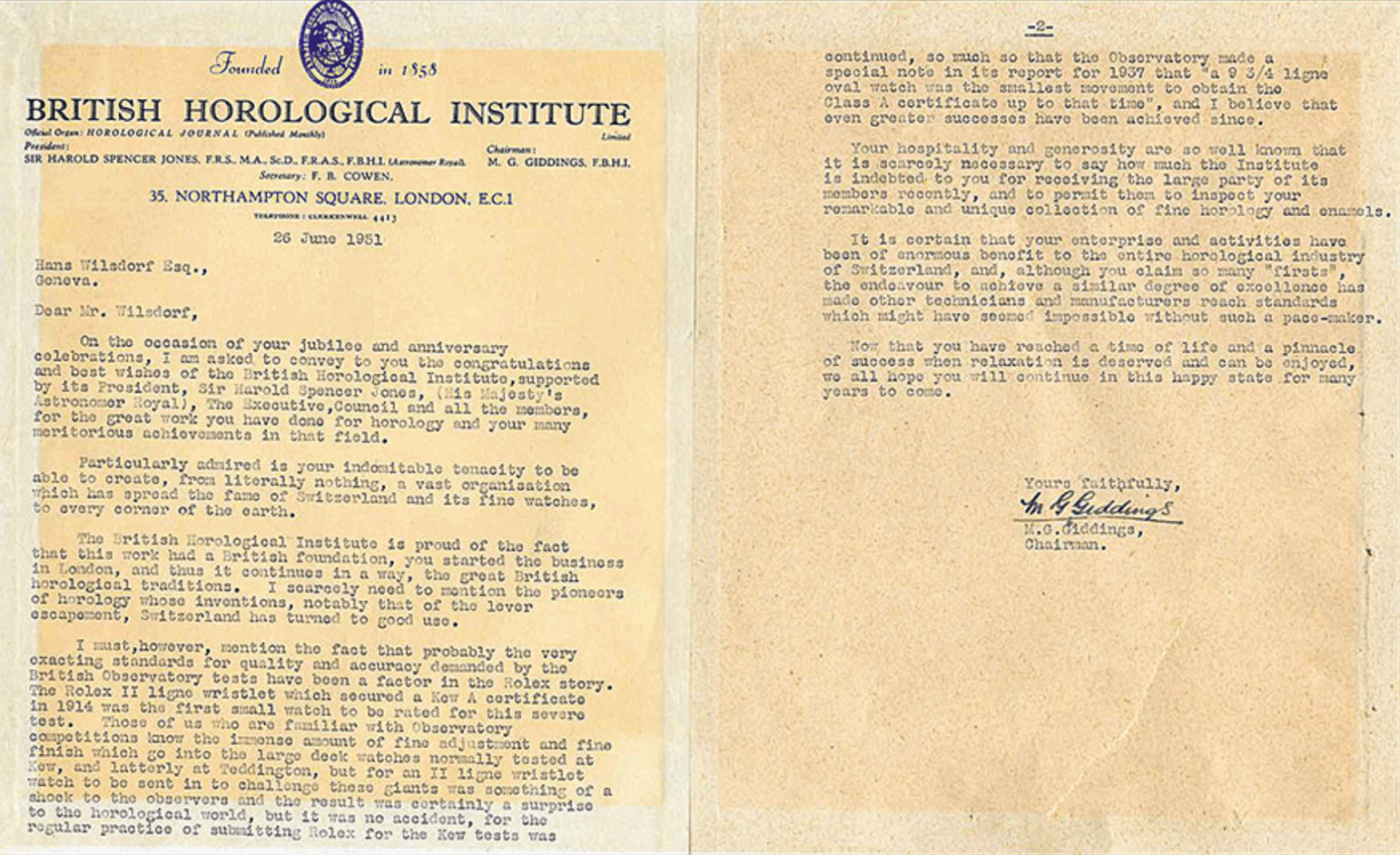

Wilsdorf’s fledgling firm was fueled by Swiss movements from Hermann Aegler and quality British cases, a fusion of precision and craftsmanship. Early on, he pursued accuracy obsessively. In 1910, a Rolex wristwatch became the first ever to earn the Swiss Certificate of Chronometric Precision, and in 1914 a tiny 25mm Rolex earned a Class “A” rating from the Kew Observatory in England: a distinction previously reserved for marine chronometers. These feats silenced the skeptics and proved that a wristwatch could rival the best pocket watches in performance. Obviously Rolex also produced pocketwatches, but his belief in wristwatches, later on, proved to be Rolex’ most important fundament.

The Rolex name began appearing on dials (a bold move when most watches carried only jeweler names), and Wilsdorf’s marketing savvy took root. After World War I, with heavy taxes making business tough in Britain, Wilsdorf moved the enterprise to Geneva, Switzerland in 1919. There he formally renamed it Montres Rolex S.A., laying the foundation for the globally renowned Swiss brand to come. Little did anyone know, this was the start of an empire; one built on precision, quality, marketing and a visionary’s refusal to accept convention.

The Oyster and the Birth of a Legend (1920s–1930s)

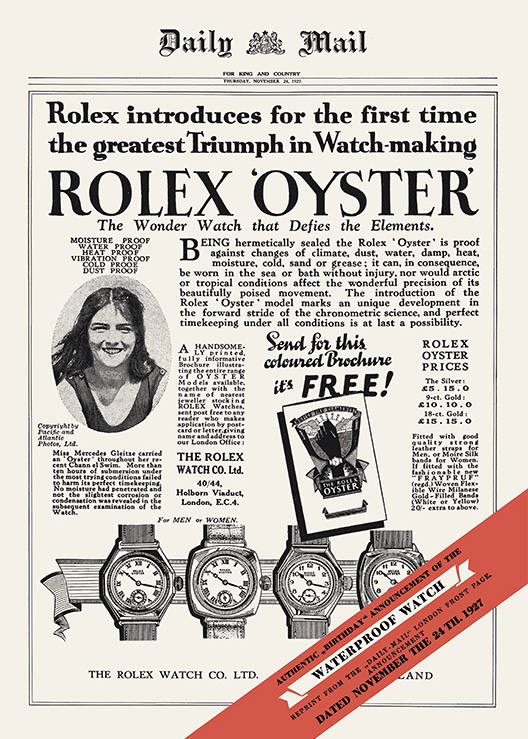

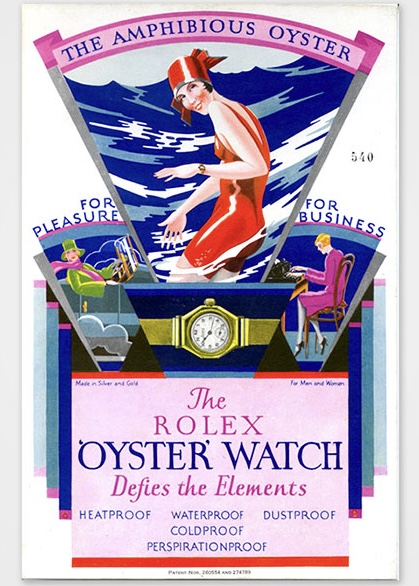

By the 1920s, Rolex was pioneering solutions to make its watches as tough as their reputation. Wilsdorf tackled a key weakness of watches at the time – dust and moisture seeping into the case. His answer arrived in 1926 with the Rolex Oyster, arguably the world’s first truly waterproof wristwatch. Using a patented screw-down crown and hermetically sealed case, the Oyster could be submerged without harm. Of course, bold claims begged for bold proof. Wilsdorf wasn’t about to miss a marketing opportunity, so he staged dramatic demonstrations; even displaying Oysters in fish tanks in store windows to show they were watertight.

In 1927, a young British swimmer named Mercedes Gleitze became the first Rolex “ambassador” in spectacular fashion. She swam the English Channel with a Rolex Oyster dangling around her neck, and after over 10 hours in frigid waters the watch emerged ticking perfectly. Seizing the moment, Rolex took out a full-page ad on the front of London’s Daily Mail trumpeting the Oyster’s success in the swim. It was pure marketing genius: the world now knew that Rolex’s waterproof watch actually worked. The Oyster had passed its trial by water, and a legend was born.

However, in order to wind the watch one had to unscrew the crown to manually provide the movement with power. Say goodbye to the waterproofness if the crown wasn,t properly screwed back on. Luckily they followed up with another game-changer in 1931. They invented and patented a self-winding mechanism with a free-spinning semicircular weight, ushering in the era of the truly convenient automatic watch. No more daily manual winding, the wearer’s natural wrist motion kept the watch wound.

The combination of the waterproof case construction and the automatic movement proved to be a game-changing success. This is why many Rolex watches still bear the inscription “Oyster Perpetual” on the dial: a tribute to these two groundbreaking innovations. Together, they remain at the core of Rolex’s enduring success.

Rolex watches soon began accompanying adventurers and daredevils, proving themselves in extreme conditions. In 1933, for instance, a British expedition flying over Mount Everest was equipped with Rolex Oysters, which performed admirably in the thin air and cold. And in September 1935, Sir Malcolm Campbell, dubbed the “King of Speed,” strapped on a Rolex as he broke the land speed record at over 300 mph at Bonneville Salt Flats. Campbell wrote to Wilsdorf after repeatedly trusting a Rolex on his record runs, praising the watch’s sturdiness under speed. These real-world exploits gave Rolex invaluable credibility. The concept of the “tool watch” – a watch built for a purpose – was taking root, and Rolex was at the forefront. By the end of the 1930s, the crown logo was quietly making its way into history, one daring feat at a time.

War, Hope and Heritage (1940s)

The 1940s were a tumultuous time globally, but also a formative chapter in Rolex lore. During World War II, Rolex gained a heartfelt sort of prestige among Allied POWs (prisoners of war). When Wilsdorf learned that captured Allied officers had their watches confiscated by the Germans, he made an extraordinary offer: Rolex would send replacements, and payment could be made after the war. In letters, Wilsdorf even insisted recipients “must not even consider settlement during the war”. It was more than a deferred payment plan, it was a bold vote of confidence in victory and an act of solidarity. Rolex ended up delivering around 3,000 watches to POW camps, boosting morale among imprisoned soldiers. Such stories cemented Rolex’s image as more than a watch: a symbol of trust and resilience. However, that’s the version history and marketing would have you believe. In recent years, though, some have begun to question the accuracy of this narrative. In fact, there are even those — like critical watchjournalist Perezcope — who argue that Wilsdorf, with his German background, may have been on the opposite side of the story altogether. Regardless, the war demonstrated that wristwatches were far more practical than pocket watches, especially those that were waterproof and self-winding.

As the war wound down, Hans Wilsdorf faced personal tragedy. In 1944 his beloved wife Florence died, leaving him without an heir. Wilsdorf responded by securing Rolex’s long-term future in a uniquely philanthropic way: he created the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation and in 1945 placed all his Rolex shares into this private trust. His intention was to ensure the company’s profits would be reinvested and also used for charitable causes, rather than enrich shareholders. To this day, the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation owns Rolex, meaning Rolex has no shareholders to appease and can follow its own vision. This remarkable ownership structure would prove to be one of Rolex’s greatest strengths in the decades to come, allowing a long-term perspective free from short-term market pressures.

Amidst these changes, Rolex continued to innovate. In 1945, on its 40th anniversary, Rolex debuted the Datejust, a milestone in post-war watchmaking. The Datejust was the first self-winding chronometer wristwatch that displayed the date with a disc, changing automatically at midnight. It was practical, reliable, and celebratory; launched with a Jubilee bracelet and often seen in luxurious precious metals, reflecting the optimism of the post-war era. The Datejust’s instantaneous date change at midnight must have seemed almost magical at the time, and it became an enduring symbol of Rolex’s commitment to useful innovation. Wilsdorf, ever the marketer, wanted this new model to signal that Rolex was charging ahead into the post-war world with confidence. Little could anyone predict just how big the next few decades would be for the crown.

Post-War Boom and the Iconic Fifties (1950s)

If Rolex planted seeds in the ’20s and ’30s, the 1950s was when the garden bloomed in full. This decade saw an explosion of now-legendary Rolex models – watches that defined genres and remain coveted by collectors to this day. Rolex was in tune with the spirit of the times: the world was exploring, racing, diving, flying; and there was a Rolex for each endeavor.

Consider 1953: Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay conquered Mount Everest, and Rolex was right there with them. The expedition carried Rolex Oysters on their wrists, and after the triumph Rolex proudly released the Explorer model to celebrate reaching the roof of the world. In hindsight, this story -like the POW narrative- may also have been fabricated or, at the very least, distorted to favor Rolex.

That same year, Rolex introduced the Submariner, a purpose-built dive watch that was the first wristwatch water-resistant to 100 meters. With its rotating bezel to time decompression stops and bold luminous markers and hands, the Submariner quickly set the standard for all dive watches to come. In 1954, the jet age inspired the GMT-Master, featuring a dual-timezone display. Scientists weren’t left out either – Rolex unveiled the Milgauss later in the 50’s, designed to resist magnetic fields in labs and power plants. And perhaps the crown of ’50s elegance, the Day-Date arrived in 1956 as well, the first watch to spell out the day of the week alongside the date. Crafted only in precious metals and soon nicknamed the “President,” the Day-Date became the wrist-wear of CEOs, presidents, and visionaries. Not to be overlooked, Rolex also introduced a Lady-Datejust in 1957 so that women could enjoy the brand’s flagship date watch in a smaller size.

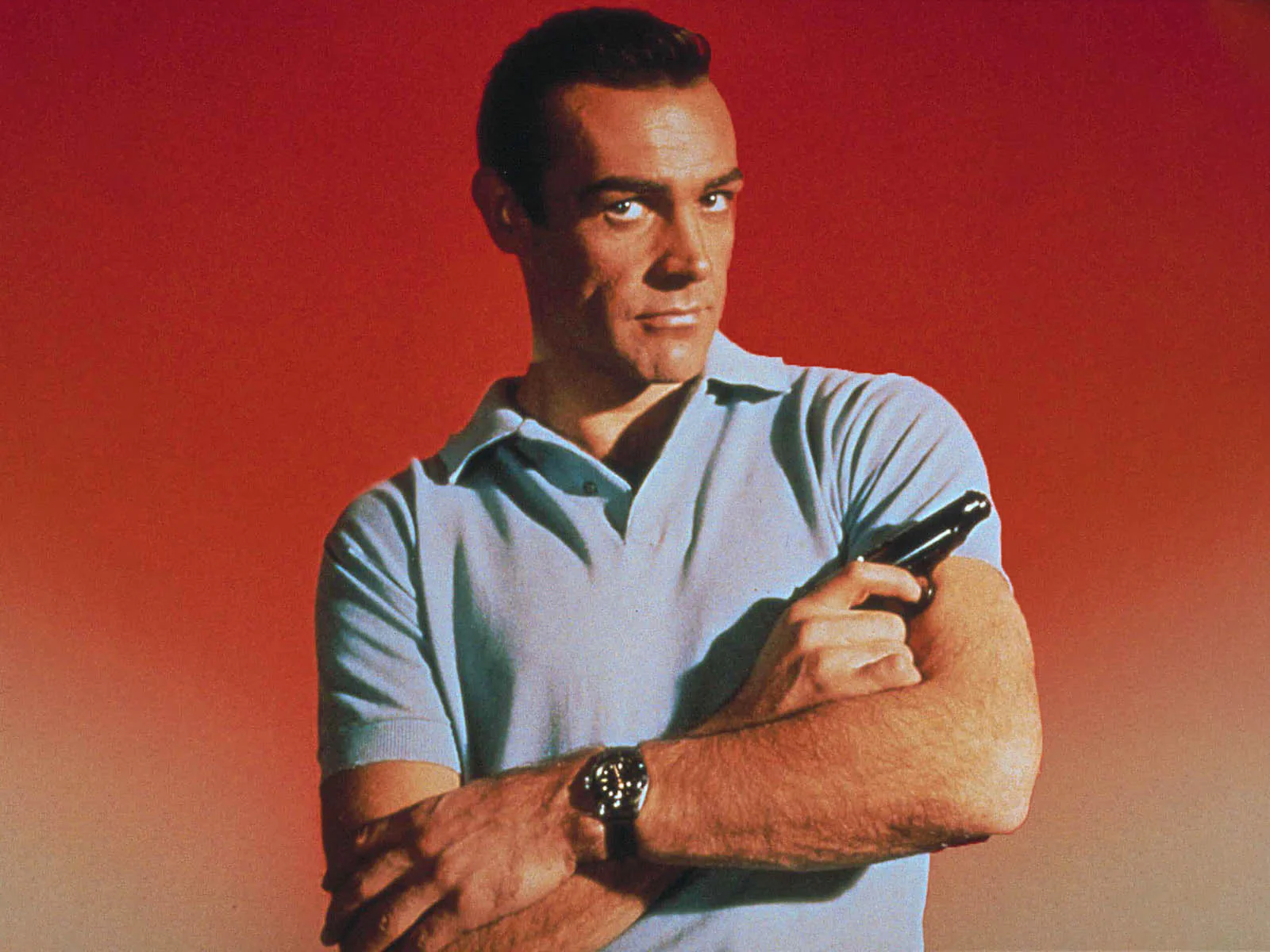

By the end of the 1950s, Rolex’s lineup had essentially defined what a “sports watch” or “tool watch” is. The strategy was subtle but brilliant: aim watches at professionals who genuinely needed them, and the broader public will covet them as well. A Rolex for divers, pilots, mountaineers, scientists, and leaders; it gave the brand a halo of adventure and prestige. Popular culture took note too. In 1962, the very first James Bond film Dr. No hit theaters, featuring Sean Connery sporting a Rolex Submariner on his wrist. Both Bond and the Submariner were nascent icons then , no one could have predicted the immense success of the 007 franchise or the Submariner, but seeing the suave secret agent with a rugged Rolex cemented the watch’s image as the ultimate do-anything, go-anywhere timepiece. The ’50s firmly established Rolex as the it watch for achievers, whether real or fictional.

“Evolution, Not Revolution” – The Heiniger Era (1960s–1970s)

In 1960, as the world entered a new decade, Rolex’s founder Hans Wilsdorf passed away at age 79. Thanks to his foresight, the company didn’t miss a beat. It was already securely owned by the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation and managed by trusted associates. In 1963, leadership passed to André Heiniger, a charismatic figure who had joined Rolex in the 1940s and understood Wilsdorf’s ethos inside and out. Heiniger would lead Rolex for the next three decades, steering the brand through one of the most challenging periods in watchmaking history. Under his guidance (and later his son Patrick Heiniger’s), Rolex famously embraced a mantra: “evolution, not revolution,” a phrase Patrick Heiniger himself used. What did that mean? In essence, Rolex would not chase wild trends or radically reinvent its models each year. Instead, it would focus on steady, incremental improvements, refining what it already did best. This conservative, long-term approach, made possible in part by Rolex’s unique no-shareholders ownership, kept the company on course even as others faltered.

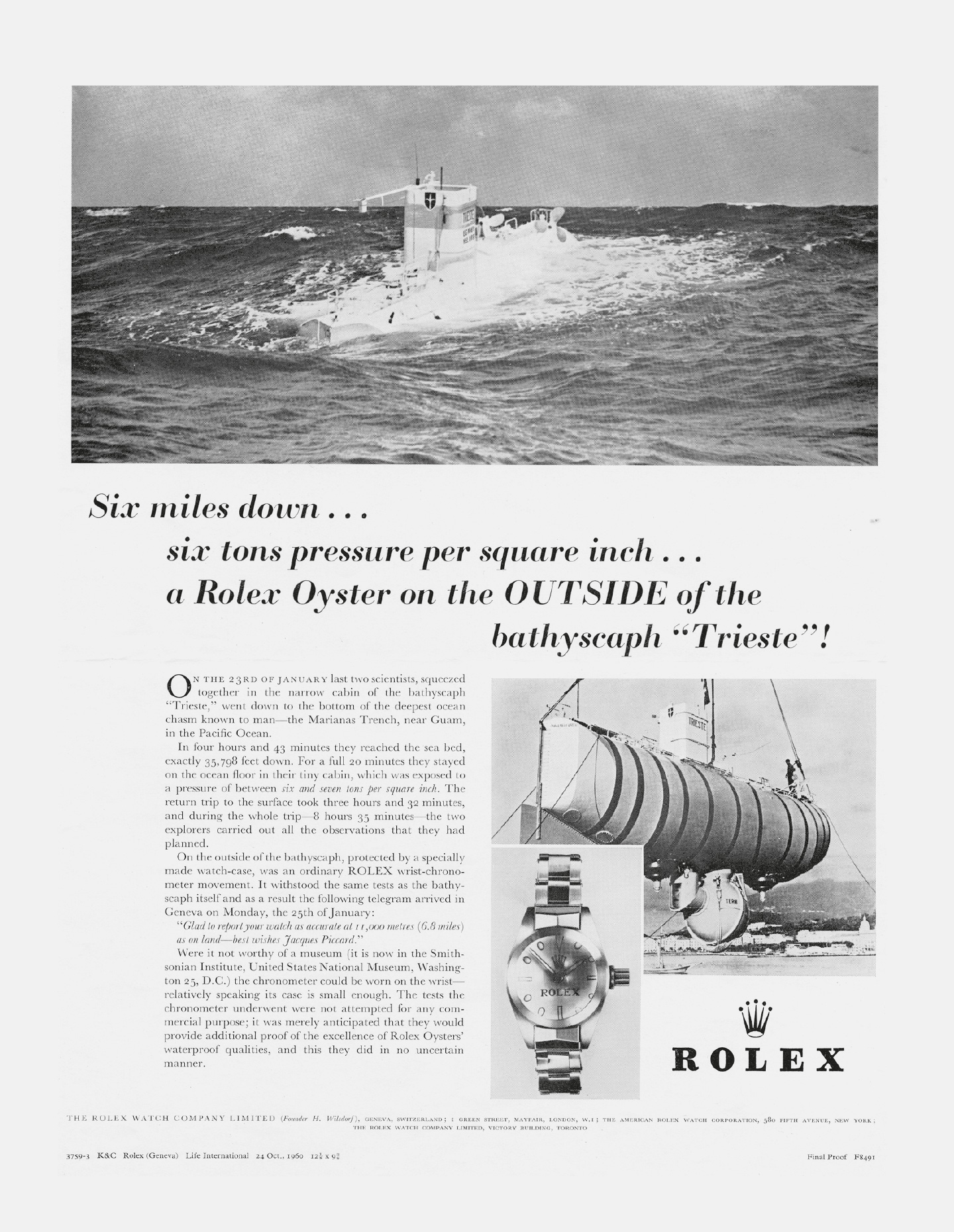

That’s not to say the ’60s lacked excitement for Rolex. In fact, 1960 itself started with a literal deep dive into history: In January of that year, the U.S. Navy’s Trieste bathyscaphe descended to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest point on Earth’s oceans, and strapped to its exterior was a special experimental Rolex. The watch (later dubbed the Rolex Deep Sea Special) withstood the crushing pressure ~11,000 meters down and kept perfect performance. It was a testament to Rolex engineering, and Wilsdorf lived just long enough to see this triumph, receiving a telegram that his watch was still running at the ocean’s floor. This victory lap of durability symbolically closed the Wilsdorf era.

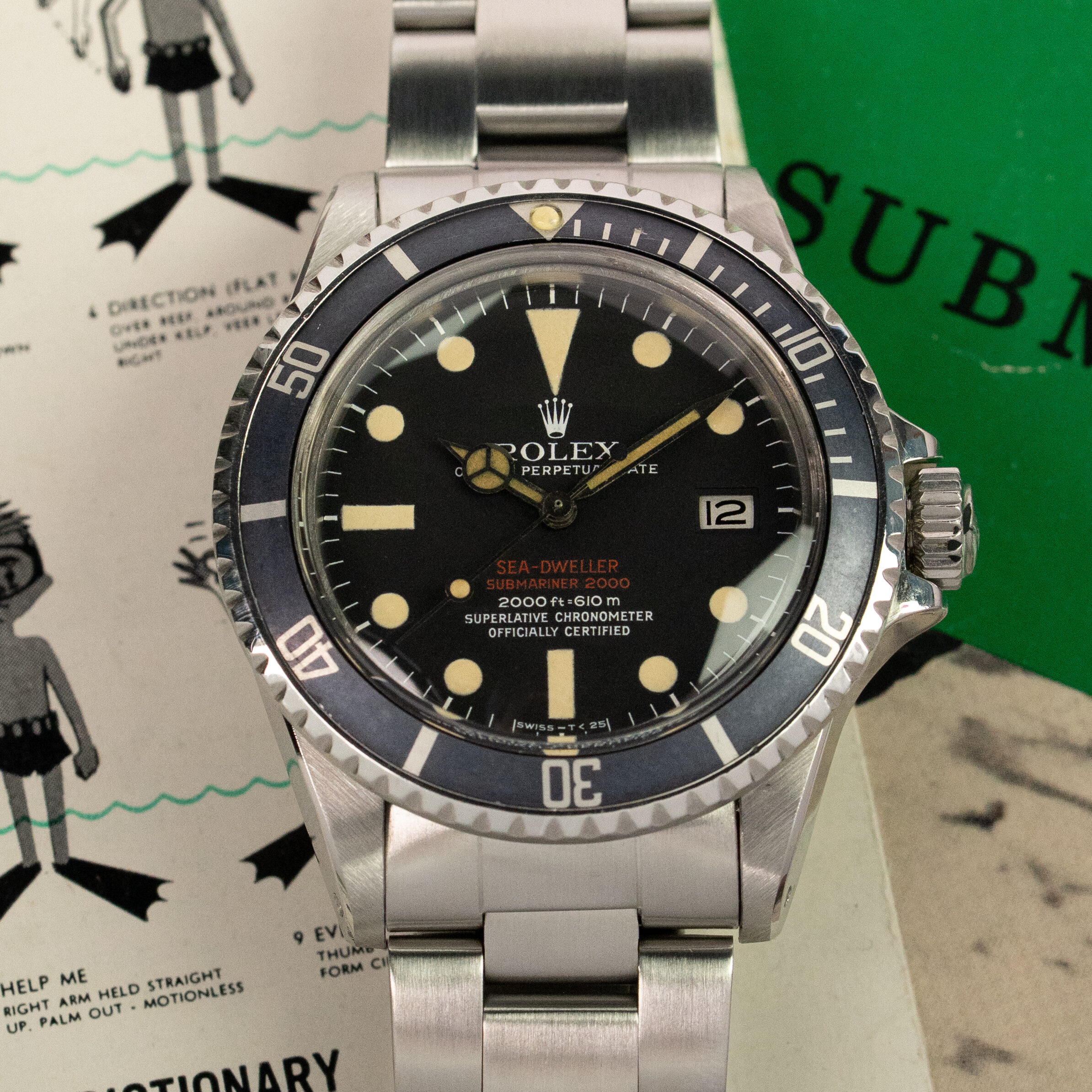

Meanwhile, in 1963 Rolex introduced the Cosmograph, a chronograph later named after the famous Daytona racetrack, aimed at the fast-driving world of motorsports. Initially, the Daytona wasn’t a superstar; manual-wind chronographs were a slow seller for Rolex, and interestingly many early Daytonas sat unsold in display cases. Little could Rolex have known that those very watches would become auction darlings decades later! But in the ’60s, the Cosmograph was simply part of Rolex’s expanding professional lineup, alongside other introductions like the Sea-Dweller in 1967, which added a helium escape valve for deep saturation divers. (after working with French company COMEX, adding this prominent organization to the list alongside CERN and Pan-Am). Rolex was covering all frontiers: land, sea, air and the race track too.

Then came the 1970s, bringing what the Swiss watch industry refers to ominously as the Quartz Crisis. New inexpensive quartz-powered watches from Asia flooded the market, offering amazing accuracy at a fraction of the cost of a mechanical Swiss watch. One by one, famous Swiss brands either went bankrupt or scrambled to reinvent themselves with quartz technology. Rolex’s response was measured and rooted in that philosophy of evolution. They did develop quartz watches, notably the Oysterquartz Datejust and Day-Date models introduced in the late ’70s, and even pionered alongisde other brands to come up with the Beta21 quartz movement. But Rolex never abandoned its core identity of mechanical excellence. They certainly did not race to the bottom or churn out cheap, disposable quartz pieces to compete. Instead, Rolex stuck largely to its lane: producing superbly built watches that exuded timeless style and quality, whether quartz or mechanical. As a result, Rolex weathered the quartz storm far better than most. Observers have noted that Rolex’s independence helped here: with no shareholders demanding quick profits, Rolex could afford patience and focus on long-term reputation. As an enthusiast might put it, while other brands panicked, Rolex kept the faithin fine watchmaking and consumers kept faith in Rolex. Moreover, Rolex already established itself, with their amazing marketing, as a status symbol, whilst the status of other brands were more alligned with their mechanical feats and accuracy.

That’s not to say Rolex didn’t innovate in this era. In 1971, for example, Rolex rolled out the Explorer II (a rugged watch for spelunkers and cave explorers), and throughout the ’70s and ’80s they gradually upgraded materials in their watches. They phased in sapphire crystals across the lineup. They also experimented with new alloys; by 1985 Rolex began using a higher-grade 904L stainless steel in some models, a super-alloy so corrosion-resistant and hard that it was more commonly seen in chemical plants than in luxury goods. (Rolex would eventually use 904L steel in all its steel watches, one of those under-the-hood improvements few noticed but which spoke to their obsession with durability.) These gradual enhancements -better bracelets, improved movements, stricter chronometer tests- weren’t flashy news headlines, but they kept Rolex at the forefront of quality. As Patrick Heiniger said, Rolex chose to be evolutionary rather than revolutionary, and in hindsight that steady approach made the brand a rock of stability when Swiss watchmaking at large was in flux. By 1980, the worst of the quartz threat had passed, and mechanical watches were finding a new life as luxury items rather than everyday necessities. And guess who was perfectly positioned at the nexus of quality, heritage, and luxury? Rolex, of course.

The Modern Classic: Rolex from the 1980s to 2000

By the 1980s and 90s, Rolex had completed a transition: from the intrepid tool watches of mid-century to the ultimate symbol of success and taste. Ironically, the very watches once built for mountain climbers and divers were now seen peeking from under starched shirt cuffs in boardrooms and at black-tie galas. Collectors and enthusiasts also began to organize, hunting down vintage pieces and swapping stories, which Rolex largely encouraged by maintaining consistency in design (today’s Submariner still clearly echoes a 1950s Sub). Through the late 20th century, the brand’s mystique only grew. For several years Rolex even topped Forbes’list of the world’s most reputable companies, a testament to how trusted that little gold crown logo had become worldwide.

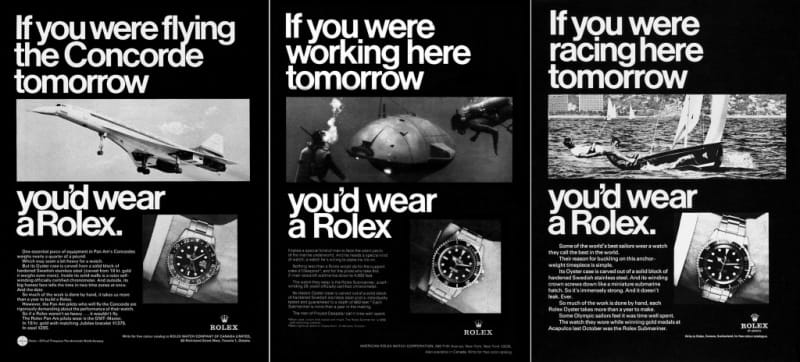

Rolex’s marketing in these years masterfully balanced aspiration and heritage. Ad campaigns reminded you that if you were flying the Concorde or exploring polar ice, you’d want a Rolex on your wrist – but even if your biggest adventure was closing a business deal, a Rolex quietly signaled you valued the best. The strategy of linking models to professions continued to pay off: a Rolex wasn’t just a timekeeper, it was a membership badge to a certain club of achievers. As one period advertisement succinctly put it, “A crown for every achievement.” By the 1990s, famous athletes, artists, and world leaders all wore Rolex, either by sponsorship or personal choice. From Steve McQueen to polo players, from Jackie Onassis to the Dalai Lama, Rolexes graced an eclectic mix of wrists. This era also saw the rise of the vintage Rolex collecting market. Models that had once been utilitarian tools or overlooked variants were now fetching attention and high prices at auctions. A telling example is the “Paul Newman” Daytona from the 60’s and 70’s. This version sports an ”exotic dial” that actor Paul Newman inadvertently made famous. In the ’90s, Italian collectors in particular drove up interest in these specific specimens. Once considered poor sellers, they became holy grails. In fact, the Paul Newman Daytona is often credited with jump-starting the entire vintage Rolex craze that is so vibrant today. This cultural shift of viewing old Rolexes as treasure added a new dimension to the brand’s story. Now Rolex was not just an object, but also a link to a rich past that enthusiasts were actively preserving.

Technically, Rolex kept improving under the radar, also by buying prominent companies (like Aegler and Gay Freres); and with it their know-how and skills. The company had always. By this point, Rolex was producing more COSC-certified chronometers than all other Swiss brands combined, an almost unbelievable statistic that underscores their scale and focus on precision. The company was also said to be worth billions and produced about half a million watches a year by 2000, yet they did so entirely on their own terms: no mergers into luxury conglomerates, no outsourcing core expertise. The foundation set up by Hans Wilsdorf continued to ensure that profits went back into the product, the brand, and charitable endeavors, rather than into investors’ pockets.

As the clock struck midnight on the year 1999, Rolex found itself not just a survivor of the 20th century, but one of its great success stories. A watch brand that began before the age of aviation was now entering the space age of the 21st century with its prestige intact and its technical drive undiminished. For us vintage watch collectors, tracing Rolex’s path up to 2000 is like leafing through a well-loved scrapbook of horological history. We see a company that innovated early and often, weathered wars and technological upheavals, and in doing so created timepieces that accompanied humanity’s triumphs large and small.

Epilogue: The Story Continues

By 2000, Rolex had already given the world nearly a century of milestones – but in many ways, it felt like the brand was just hitting its stride. The family-style stewardship (from Wilsdorf to the Heiniger father-and-son team) kept the original spirit alive, and the foundation ownership meant Rolex could stay refreshingly old-school in a fast-changing world. Collectors often speak about their Rolex watches with a personal reverence: these watches are seen as durable friends or talismans that witness our life moments. Perhaps it’s because every Rolex model comes with a backstory -a why and a when it was created- that resonates even decades later. Slip a vintage Submariner on your wrist, and you’re channeling the legacy of divers and James Bond; wear a Datejust, and you’re celebrating post-war optimism and style; cherish a battered old Explorer, and you’re carrying the spirit of climbers and adventure.

In the informal gatherings of vintage watch lovers (the kind of chat you’d find in a cozy corner of Amsterdam Vintage Watches), we often swap these Rolex tales with a sparkle in our eyes. These aren’t just products; they’re companions and artifacts: they don’t just tell time, they tell history. Rolex’s history up to 2000 is rich with innovation, adventure, and a fair bit of glamour. And so, the crown endures: a symbol of quality, a witness to history, and a source of endless fascination for those of us who cherish the romance of a historic timepiece.